Introduction

Over the last decade, the role and purpose of higher education has increasingly come under scrutiny. Faced with tight fiscal budgets, governments have often looked to the university sector as a space for potential cost saving. Even as I write this paper, the Australian federal government is attempting to tighten its financial investment in higher education by almost $3 billion dollars.[1] While this has been rejected by the Senate, the Government has made it clear that it will continue to look for ‘efficiency dividends’ and its attempts to restructure the sector will continue.

This situation is aggravated by a hostile political environment where governments are very sensitive to criticism. Historically, the intellectual freedom of universities and other civil society bodies that critique and speak on corporate and governmental power has been valued. With a traditional strength of the university community holding powerful interests to account by demanding evidence-based policy, the rise of ‘anti-intellectualism’ encased by political populism now places universities in a precarious position.[2]

A third trend impacting the university sector is the demand to establish ‘job ready’ graduates. This has meant that university curriculum has increasingly been asked to incorporate ‘soft’ or ‘transferable’ skills. In an overcrowded curriculum, combined with the demise of the TAFE (Technical and Further Education) sector, the pressure for universities to reposition themselves in this way is increasing. But such a request is seen to challenge the traditional ‘intellectual pursuit’ of universities.

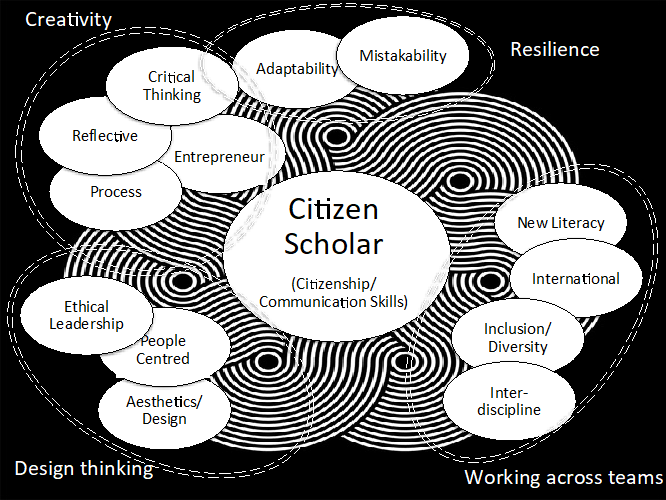

It is from these multiple perspectives that universities are now being forced to reflect on their role and purpose, and ask ‘why do we exist?’ Over the last few years, it is this question that has been driving my research, teaching and community engagement. Working with collaborators across the world, we have developed the concept of the ‘Citizen Scholar’ (see Arvanitakis and Hornsby 2015). A key focus has been to respond to the on-going structural changes driven by global and technological advancements, changing social, political and economic environments with the aim of ‘future-proofing’ higher education by looking beyond the provision of content alone and focusing on a new set of ‘Graduate Proficiencies’ for the century ahead (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Citizen Scholar (sourced from Arvanitakis and Hornsby 2015)

Figure 1: The Citizen Scholar (sourced from Arvanitakis and Hornsby 2015)

The Citizen Scholar

The Citizen Scholar encapsulates the idea that universities exist to both promote scholarship as well as active and engaged citizens. That is, universities need to inculcate a set of skills and cultural practices that educate students beyond their disciplinary knowledge. This arguably pushes the debate beyond the simple transfer of skills, as part of the activities and academic development necessary to compete a degree. It also goes beyond the ‘soft skills’ debate that dominates much discussion.[3] Rather it takes on a broader, more social focus.

This is driven by the idea that universities must maintain a social mission that mobilises knowledge for the benefit of society. That is, a central purpose of higher education is to improve the societies in which we live and foster citizens who are creative, innovate and have the ability to critique the structures around them with the purpose of community betterment.

Inspiration for the Citizen Scholar is derived from Gramscian views on education and intellectuals and Freirean pedagogical aspirations. Italian theorist, Antonio Gramsci, argued that education must be about promoting social change and challenging traditional power relations. Unlike modern day interpretations of the term “intellectual” which suggest elitism and reinforce social hierarchies, Gramsci (1971: 10) believed that anyone could be an intellectual because we all carry:

“…some form of intellectual activity …, [and] participates in a particular conception of the world, has a conscious line of moral conduct, and therefore contributes to sustain a conception of the world or to modify it, that is, to bring into being new modes of thought.”

Gramsci’s position was that the process of education was not about being ethereal and disconnected, but rather was rooted in “practical life” (Gramsci 1971: 10).

Though the position of universities does not figure prominently in Gramsci’s work, it is implied as the institutions of education and spaces where intellectuals gather. By extending Gramsci’s analysis, the argument is that a key role for universities is the pursuit of social change because they are inherently engaged in communities and have the potential to mobilise new sets of thinking.

Despite such noble visions, modern universities often reproduce existing power relations, particularly in a time of neoliberalism driven by differentiated fee payments and decreasing public funding. Furthermore, our content driven, discipline-specific learning environments do not encourage a pedagogy that fosters creative thinking or even societal action (Friere, 1970).

Echoing Gramsci, Friere’s (1970) vision of a pedagogy that is rooted in the lived experience – something that is increasingly relevant. Friere (Ibid) argues that we need to confront inequality through motivating students to question, challenge, and agitate around existing power structures. Friere believed that education was about addressing the needs of the masses and to teach them to make a better society by addressing inequality. But what is additionally inspirational, and reinforces the vision for the Citizen Scholar, is how Friere identifies that the way we teach needs to connect with problems surrounding us and who we teach needs to be diverse:

No pedagogy which is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed must be their own example in the struggle for their redemption. (Freire, 1970: 54)

If we interpret the messages of both Gramsci (1971) and Friere (1970), we must ensure that our learning environments establish a pedagogical frame that integrates a sense of moral and ethical purpose to learning; that actively integrates cultural pluralism in developing knowledge and understanding that aspires to liberate the learner from existing power structures by fostering a desire to challenge and change the social system in which we live; and that connects the reality around us and its many problems to the knowledge generation process.

Technology and the Citizen Scholar

Education technology is an important mechanism in achieving these goals. Technology, when employed correctly, can open up pathways that both connect and empower our students. Notably, as established academics and researchers, many of us already do this in our intellectual projects. We tend to be problem-oriented and push for change in our research. We seek to challenge existing power structures and influence how society is shaped. We do not treat knowledge as uniform, appreciating that context is important and we take evidence seriously in the knowledge generation process.

The challenge is to ensure that we follow such a path in our learning environments. We should not let the dominant pedagogical model focus on disciplinary content transfer. Nor should we privilege lecture spaces in which individuals stand up at the front and speak at, rather than with, students. Despite this, many of us still do. As such, we must challenge these structures and expect more from our learning environments. To do this, we need a pedagogical stance that moves us towards a practice that fosters Citizen Scholars of our students.

Though there many ways we can interact with technology to achieve the pedagogical stance of the Citizen Scholar, here I will focus on two. The first is to ensure that we are pedagogically driven rather than technology driven. Technology should be seen as a delivery mechanism of our pedagogical strategy rather than a strategy in and of itself. If we refer to some of the Graduate Proficiencies highlighted in Figure 1, we can see that ‘internationalisation’ is fundamental in preparing the Citizen Scholar. This involves working across cultures, in different cultural context as well as cultural competence and ‘cultural humility’ (Nomikoudis and Starr 2015).

The appropriate employment of technology can allow us to ensure that our students connect across the world and different cultures. We can establish student project teams that cooperate and share lessons as well as learning materials. Our students can become culturally competent not through some ‘tick the box’ approach, but by embedding learning across the curriculum.

The second is by operationalising the ‘new literacies’ proficiency. That is, the use of technology, design and systems thinking, as well as understanding how programming languages work should be seen as the fourth dimension of literacy – taking us well beyond reading, writing and arithmetic. This is fundamental in both ensuring employability skills but also understanding that much of contemporary citizenship also happens in an online environment.

Despite its many downsides, the internet as a space of democratic interaction is incredibly valuable. It must be fostered, and should be part of any civics education program, for its speed, its links to such a vast array of information, its uptake among young people and its capacity to break down social barriers and equalise interactions.

This means that the space itself is not the problem; the challenge is in the approach we take to etiquette. This includes ensuring that we provide the civic skills to interact meaningfully and allow for disagreement through social media and other forums as spaces for engagement. Many institutions have developed “netiquette” guidelines, as well as the skill to self-police bullies and trolls. This is social etiquette at its egalitarian best in that it was developed and monitored by the people who populate the space.

Beyond the social is the political. Political processes have been slow to catch up to the online world. For example, online petitions gather hundreds of thousands of signatures, but where are the vehicles for these voices to be heard? For the internet to be a truly democratic space, our democratic institutions (including universities) must recognise its “real world” presence. Genuine interactions online may be different in nature, but are no less real.

The Citizen Scholar has education technology at its core. This is not technology for technology’s sake, however. Rather, the call is for technology that is driven with pedagogical intent and focuses on developing graduate proficiencies as well as engaged and active citizens. Anything less will not only fail our moral obligation to students, but will leave open the question, ‘why do universities exist?’

[1] http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/turnbull-governments-28-billion-university-funding-cuts-shot-down-by-the-senate-20171019-gz47yf.html

[2] http://upp-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1849-Foundation-Glyn-Davis-Lecture-Report-v1.pdf?utm_campaign=website&utm_source=sendgrid.com&utm_medium=email

[3] http://www.afr.com/leadership/management/business-education/universities-teach-soft-skills-employers-want-to-students-of-hard-disciplines-20170328-gv89hq

Latest posts by James Arvanitakis (see all)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours