by Stephen Pinel

We read and hear a lot about authentic learning and engagement in education these days but the concept of authenticity is rarely well defined. What is authenticity and how can we use authentic work to improve student engagement?

Authenticity is the key in being able to successfully engage students in their own educational outcomes. Students that are authentically engaged are students that take responsibility for their own learning, retain and can apply knowledge in other contexts, and care more about their own educational and cognitive development than about the formal outcomes, or grades, that are achieved. The more our students become engaged in their education, the more they care about their learning, and the less they care about their grades.

In order to engage students, we must be able to understand our students, and be able to select appropriate instructional techniques for each particular context. A solid understanding of the links between learning theory (how students learn) and instructional theory (how to help students learn) which informs instructional technique is critical to this process.

What makes work ‘Authentic’?

Students, particularly at high school, are very switched on to identifying work that they feel may add value to their life, and work that they see simply as ‘busy work’. Teachers will sometimes create work that mimics real life activities (the maths classic – how much paint is needed to paint the house), but in my experience, students do not always see these activities as authentic (i.e. engaging).

Consider authenticity in the context of musical performances. How do we decide whether a band like Bjorn Again (an ABBA tribute band) is authentic? Ultimately, each claim of authenticity is tested and validated by the audience, not the performer. It follows, then, that as much as we as teachers may design lessons and units to be authentic, their actual authenticity will not be validated until we bring them to the students. That is, a topic or problem being authentic is not, of itself, sufficient to allow authentic learning to occur. The topic or problem must also be seen to be authentic by our students.

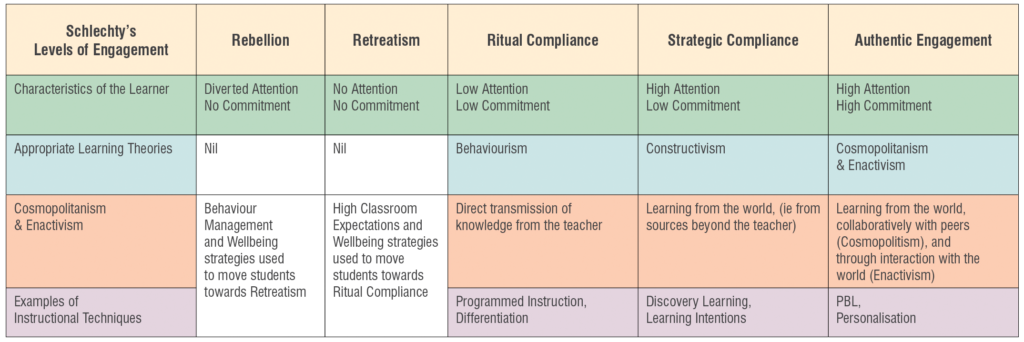

One of the characteristics of an authentically engaged student, according to Philip Schlechty, a researcher in engagement, is that knowledge is retained after the fact of assessment for grades. There are students in our classrooms who may appear to be engaged in school work but work hard primarily to receive good grades, rather than for the learning itself, and soon forget the knowledge they have learnt. They are described by Schlechty as being strategically compliant (see Table 1), rather than authentically engaged. This appears to be an important distinction between these students and students who see their work as authentic, in that it has value beyond the classroom.

Schlechty’s model of engagement can be used it identify which learning theories are appropriate to use in different contexts, and with students at different levels of engagement. It helps us to understand our students and measure their levels of engagement so that we can use appropriate teaching styles to maximise learning, and hopefully improve their level of engagement over time.

Learning Theories and Instructional Theories

Learning theories are systems of ideas that are intended to explain the way in which we observe how students learn. Instructional theories are used to explain how the various observed teaching techniques work to help student learning. There are some natural links between some learning theories and instructional techniques.

Behaviourism

Behaviourism as a learning theory can be described as direct transmission of knowledge from teacher to student. It follows from this that behaviourism does not require interaction between learners, or even between learners and actors outside of the classroom. Programmed instruction, explicit instruction and direct instruction are all teaching techniques that are based on behaviourism as a learning theory. Each of these techniques make it very clear to students what is expected for them to succeed, but give students no ownership of learning, and so tend to result in low commitment, other than what is immediately required for each lesson. Proponents of these styles of instruction often value teacher accountability, and describe these techniques as evidence-based in terms of producing improved results. However, accountability as a strategy for improvement is a relatively poor way to look for improvements in outcomes. If teachers are primarily accountable for the data and results they produce, then that will become the focus. Behaviourism, as a learning theory, works well for students who are working at the level of ritual compliance, in that they have low commitment and attention, but will do what is asked by the teacher in order to avoid negative consequences.

Constructivism

Constructivism as a learning theory assumes a greater role for relationships between learners and the world than in behaviourism. The teacher is no longer the only source of knowledge or facts, and students construct knowledge gained both from the teacher and from their own experiences and sources outside of the classroom. As in behaviourism, the world exists independently of us, however there is an acceptance in constructivism that it cannot be well defined. Programmed learning and similar forms of instructional techniques used in behaviourism are inappropriate. However, students may still be guided in their learning by the teacher, so the provision of clear learning intentions and success criteria can be useful instructional techniques to allow students to judge their own success as learners, although the criteria for success are still set by the teacher rather than the students themselves. Students that show a high level of attention, but without ownership of their own learning, learn well under constructivist learning theories, and can best be described as strategically compliant under the Schlechty model for engagement.

Cosmopolitanism

In some ways similar to constructivism, cosmopolitanism as a learning theory also posits that students construct knowledge by reorganising information from a variety of sources, including the classroom teacher and other sources such as their own experiences. Cosmopolitanism differs from constructivism in that cosmopolitanism describes learning as a collaborative activity, and occurs as students collaboratively engage with the world. Cosmopolitanism implies an openness to ideas and cultures that are different to our own, as a result of interaction with other people, cultures and ideas. This requires from students a high level of commitment in order to reorganise existing schema to accommodate different ways of thinking, however it can result in more enlightened and mature students, as their high level of work commitment causes a similarly high level of commitment to alternate cultures and ideas. Instructional techniques appropriate for behaviourism are certainly not appropriate, and even learning intentions and success criteria need to be personalised, or negotiated between teachers and students. Interaction between students and other cultures can be assisted through e-learning and digital pedagogies. Under the Schlechty model, students working at this level are authentically engaged, as they are frequently directing their own learning, for their own purposes.

Enactivism

The key difference between cosmopolitanism and enactivism is that while cosmopolitanism focuses on collaborative learning through observations and interactions with the world at large, enactivism also identifies actions that result from that learning as a part of the learning process. In other words, the learning process can itself result in action that changes the world we are studying. Enactivism will obviously only be relevant for students that are highly committed to their studies in a personal way and own their education as a way to improve the world. These students are also identified as being authentically engaged in the Schlechty model, as students highly committed to their own learning. Project based learning is an effective way for students to learn about their world and learn how to make changes to the world at the same time. While designed for first year engineering students, the Engineers Without Borders Challenge is an example of the sort of instructional technique that embodies enactivist thinking (Engineers Without Borders, 2014).

Levels of engagement

Measuring student engagement accurately can be a difficult task. Schlechty has developed a model that identifies five different levels of student engagement, from rebellion to authentic engagement. Student engagement is measured on two domains, attention and commitment, where only students who show high attention and high commitment are identified as being authentically engaged. The characteristics of the various learning theories described above match the needs of students at different levels of engagement as well as appropriate instructional techniques as shown in Table 1.

Stephen is Head of Science at Unity College, Caloundra. He was previously Head of Science at Proserpine SHS where he was heavily involved in eLearning, leading a team of eLearning Mentors to develop innovative and engaging curricula school wide. Stephen has taught in both the independent and state sector in Queensland, as well as abroad in the UK and at the Rotterdam International Secondary School. He blogs on engagement at http://wsen.edublogs.org

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER [mc4wp_form id=”4523″]

Latest posts by Education Technology Solutions (see all)

- Network Technologies Driving Sustainability for Education and Hospitality in 2025 - May 6, 2025

- Keypath Education Launches AI-enabled Short Course Platform to Drive Career Progression for busy Professionals - February 19, 2025

- Lumify Work Partners with AI CERTs™ to Bring Cutting-Edge AI Certifications to ANZ & PH - February 5, 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours