A growing and perpetual challenge schools will face in their digital evolution is that of successfully cutting through the immense and often very sophisticated hype associated with all emerging digital technologies, to acquire the technology needed and to avoid wasting scarce monies, social capital and teachers’ time with the unnecessary and the ineffectual. This is where the principal’s digital acumen is tested.

While the technology companies have over the last century plus displayed considerable marketing expertise in winning over the school market globally (Lee & Winzenried, 2009) their efforts in recent years have become that much more sophisticated – and in some instances one might say insidious. Most of the companies are simply doing their utmost to sell their product. However, recent studies on a development known as edubusiness indicate a few companies could be using their involvement in educational testing to validate the selling of their instructional technology. The studies by the likes of Hogan (http://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/11666, http://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?tag=anna-hogan) and Lingard (http://www.educationincrisis.net/blog/item/1243-complementarities-and-contradiction-in-the-pearson-agenda) provide an insight into the techniques some of the multinationals employ to secure and hold the school’s custom. These studies underscore why the head, as the chief school architect and final decision maker, has to be able to cut through the technology hype, and why it is vital the school has a chief digital officer (CDO) who can provide the requisite expert advice (Lee, 2016).

Those studying the evolution of digital technology in schooling have observed the finite hype cycles of all the major instructional technologies over the last fifty plus years, the often still very considerable gap between the technology rhetoric and the reality, and continue to watch schools and governments spend vast monies on dated and dubious technological ‘solutions’.

Schools, education authorities and indeed governments globally have over the last forty plus years wasted millions of dollars acquiring inappropriate and unnecessary digital technologies. They continue doing so today. Election after election, globally one sees the ‘in technology’ offered up to the voters. The poor decision making is not only costly, but also wastes teachers’ time and impairs the productive use of the apt technology.

Disturbingly, this has been so with all manner of instructional technologies since the magic lantern (Lee & Winzenried, 2009) and is likely to continue until schools – and principals in particular – exercise the requisite acumen and leadership in shaping the desired totality.

How great that waste of money and time has been no one knows. Suffice it to say anyone who has been associated with digital technology in schools for any time will be aware of the monies that have been and are currently being wasted, the staff’s frustration of being lumbered with inappropriate technology and the damage caused to the digital evolutionary quest when ill-conceived decisions are inflicted on the school. For example, in the recent elections in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) the subsequently successful Labour Party pledged to provide every student an iPad. This one-size-fits-all approach, that would be controlled by the government’s ICT experts, without regard to each school’s situation was offered to some of the most affluent electorates, in one of the world’s most affluent nations. No thought was seemingly given to the reality that virtually every child in that wealthy city state already had a suite of personally selected digital technologies, that the children from a very early age had already normalised the use of digital 24/7/365 and that the government was both duplicating the home buys and imposing a ‘solution’ that would stymy the digital evolution of its schools.

Sadly, the ACT scenario is being replicated worldwide, probably daily by other governments, education authorities and schools. All are still focusing on the parts and not the creation of the desired tightly integrated digitally-based ecosystem (Lee & Broadie, 2016).

It takes astute decision makers, supported by apt processes, to acquire and secure access to the digital technologies required, to see through the hype and spin, to reject the unwarranted and to minimise the waste and maximise the effectiveness of the technology. It requires them to be very good crap detectors.

Fortuitously, it would appear the first of the schools have attained a digital maturity and an understanding of the desired totality where they can markedly minimise the risk of acquiring unnecessary technologies, while simultaneously ensuring their staff and students have the digital tools and resources required.

That said, it is impossible for schools not to make mistakes. Digital evolution and transformation is by its very nature risky, the way forward uncertain and, while digital technology has improved markedly, there is still often a large gap between the promised and actual performance. Mistakes, some substantial, were made by all the schools studied. All one can ever do is to minimise the risk.

That risk can be markedly reduced by:

- giving schools the power and responsibility for acquiring the digital instructional technologies they require, getting the central-office ICT experts out of the play with the personal technologies (Lee & Levins, 2016) and having the latter focus on providing the bandwidth and, where apt, the network infrastructure. Be willing to say no to undesired technological solutions offered by the ICT experts, be they in or out of house.

- ensuring the principal and CDO oversee all major digital technology buys. All buys should enhance the desired school digital ecosystem and as such one needs a whole-of-school digital technology budget, and most assuredly not the traditional discrete faculty/unit budgets.

- moving the school to an increasingly mature digital operational base, distributing the control, empowering the school’s community and having everyone better understand the role that the balanced use of digital and social networking can play in creating the desired culture and digital ecosystem. Having all, rather than a few ‘experts’, understand the desired role of the technology is vital.

- pooling the digital technologies of the students’ homes, the school and its community and distributing the risk, particularly with short life cycle technologies. Schools do not have to own the desired personal technologies to acquire them. Indeed, it is far wiser not to buy them, except in special circumstances.

- adopting a bring your own technology (BYOT) policy and, in turn, normalising the whole-of-school use of the students’ own suite of evolving digital technologies. BYOT – and having each student select, acquire, support and upgrade each of his/her chosen suite of hardware and software – places control in the hands of each user and largely removes all the risk for the school and government associated with most of the short-life personal technologies. With BYOT, the school basically removes from its remit the near impossible task of continually funding and selecting the desired personal technologies for each child, while at the same time empowering its clients. By all means, offer advice, but the school and government no longer have to worry about all the hype and risk surrounding the plethora of short-term personal technologies.

- appreciating that the richness of the educational resources on the Internet and the multimedia digital creation facilities and apps in the students’ hands significantly reduces digitally-based schools having to buy packaged teaching resources – digital or print.

- networking or working collaboratively with other ‘educational’ services, distributing or totally removing the risk to the school.

- renting apt Cloud or app services. Many schools have built very extensive and expensive hosting facilities, the services on which have to be continually updated, with the associated risk and costs. The rental of continually upgraded apps and Cloud-based services removes much of that hosting cost and the many associated risks.

It also helps if the leadership:

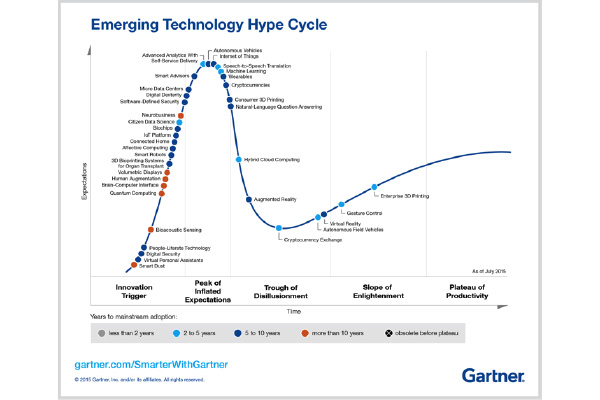

- understands the Gartner Hype Cycle (Lee & Winzenried, 2009) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hype_cycle) and those technologies whose life cycle is shortening. While pointed out, it is highly obvious that all instructional technologies will move through a finite life cycle, at the beginning of which is the hype stage. Appreciate that most of the emerging technologies will have an increasingly shorter life cycle.

- avoids the acquisition or leasing of short life cycle digital technologies. The prevailing perception of most schools and the auditors is that the technology will remain current for years. The fact that it will not and will soon be superseded needs to be understood.

- recognises the total cost of ownership of the technology and the importance financially, operationally and user wise of very high reliability, low maintenance and the ease of being integrated in the school’s digital ecosystem.

- is aware of the moves by the major technology companies globally to ‘own’ the school and its data, their desire to ‘hook’ schools financially into long-term financial commitments and is very wary about entering into any long-term financial agreements with those technology companies.

- is continually alert to the likely unintended impact and benefits that will flow from the 24/7/365 use of digital and the importance of optimising the desired benifits (Lee & Broadie, 2016).

The ability of the head – with the help of the CDO – to cut through the hype is a critical skill required in digital schools. The failure to do so can at the extreme, as too many schools and education authorities have found, bankrupt the school or at the very least deprive the school for years of scarce resources. That is an unwarranted risk that can be easily avoided if the school’s leadership continually asks if the suggested new technology will enhance the school’s digital ecosystem and pays heed to the advice mentioned above.

For a full list of references, email info@interactivemediasolutions.com.au

Mal Lee is a former director of schools, secondary college principal, technology company director and now author and educational consultant. He has written extensively on the impact of technology and the evolution of schooling.

Roger Broadie has wide experience helping schools get the maximum impact on learning from technology. He is the Naace Lead for the 3rd Millennium Learning Award. In his 30-plus years of working at the forefront of technology in education, he has worked with a huge range of leading schools, education organisations and policymakers in the UK and Europe.

Latest posts by etsmagazine (see all)

- Introducing the MOBIUZ Ultrawide Curved Gaming Monitor – The Next Evolution in E-Gaming - January 28, 2022

- Technology For Inclusion With Diverse Learners - December 3, 2019

- 2020 Vision for Interactive Learning in Tomorrow’s Classroom - April 29, 2019

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments

Add yours