The Commonwealth Government program, known as the Digital Education Revolution, has now been underway for five years. It was announced as a major election commitment by the Australian Labor Party during the 2007 federal election. Implementation of the program was made an immediate priority by the newly elected Labor Government. What has been achieved since then? What does the future hold?

The first thing to be said is that the program has achieved what it set out to do. The core 2007 commitment of then opposition leader, Kevin Rudd, was to fund Australian schools to provide a computer on the desk of every upper secondary school student, revolutionising their classrooms with new or upgraded ICT equipment. (A Digital Education Revolution, ALP 2007)

Initially, one billion dollars was committed to deliver this pledge. This has grown to an investment of over $2.1 billion. Through the National Secondary School Computer Fund, schools and schools systems have been able to install more than 911,000 computers, exceeding the original target of 786,000 computers by the beginning of the 2012 school year. The Fund provides funding of $1000 per computer and up to $1,500 for the installation and maintenance of that device.

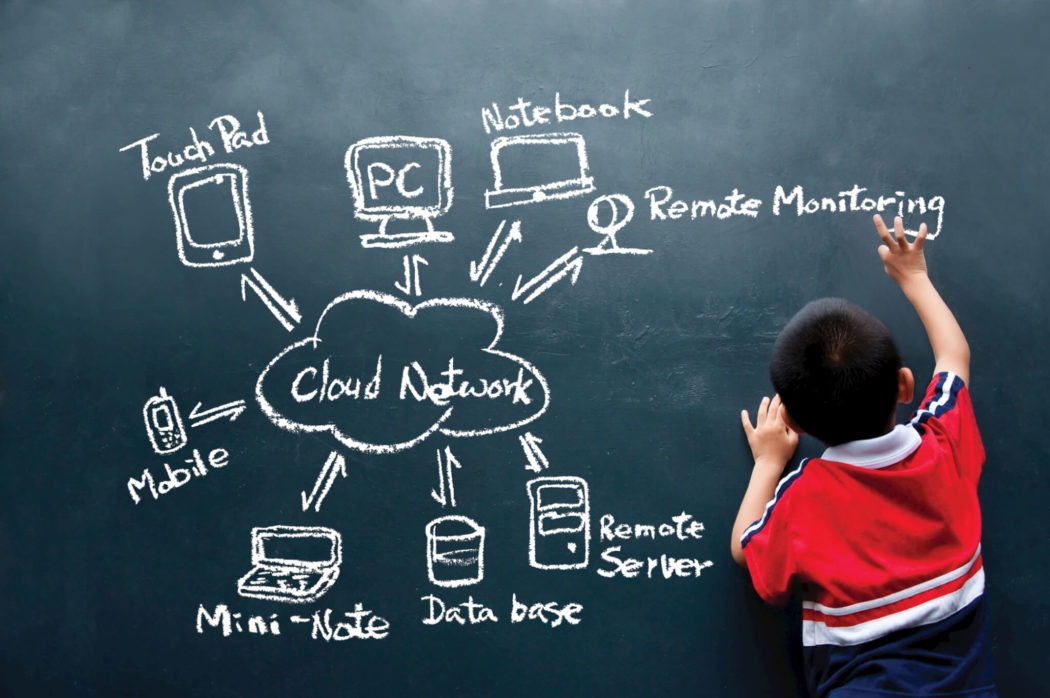

The program has operated flexibly and schools have been able to purchase a mix of devices, including netbooks, laptops, tablet computing devices and desktop computers. Funding was also provided to cover supporting infrastructure, such as in-classroom, wireless networking.

The NSW Government schools provide a powerful example of the scale of change that has resulted. Before the start of the program, students in those schools had one of the lowest computer-to-student ratios in the country. Now all NSW Government school students are issued with their own netbook at the start of Year 9. The devices are issued to them personally and are retained after they leave school.

The netbooks are pre-loaded with complete software suites. Infrastructure funding allowed the NSW Government to provide fully-supported, integrated wireless networking in all classrooms through a project which was, at the time of installation, the second largest integrated wireless networking roll out of its type in the world. Somewhat dauntingly, the organisation behind the largest such roll out was the United States Navy.

The website of the NSW Department of Education and Training provides some examples of the changes this has brought about. At Bathurst High School, Year 9 students used real-time data from the internet to track volcanic activity in North America. They were also graphing data, videoing their own experiments and measuring reaction times – all using the new technology.

While textbooks will never be able to offer consistently current data, students with their own laptop and internet connectivity have up-to-date information at their fingertips whenever they need it. The Bathurst students discovered the laptops could enrich any subject. In Japanese studies, for example, they downloaded a kanji (Chinese characters used in modern Japanese) writing tool and were writing with Japanese symbols in their Word documents, and also recording and critiquing their own speeches in Japanese.

At Cherrybrook Technology High School, a science teacher with more than 10 years’ experience has been helping to integrate student laptops and other new technologies into Year 9 classrooms. As a curriculum expert, she has also looked at research from around the world about how technology changes students’ experience of school, and she says the findings are amazing. She particularly draws attention to, “The one thing that is common across all the research into interactive whiteboards and laptops for individual students…how engaged, motivated and interested in the schoolwork most kids become.”

The same teacher notes that there have always been challenging concepts that students find difficult to understand but, thanks to technology, these concepts are now within their grasp. For example, students frequently confuse the concept of ‘dissolving’, with ‘melting’ which is an important concept in chemistry. The reason for the confusion is that kids have real difficulties in going from what they can see (like blue copper sulfate dissolving in water) to a written equation that represents what they can’t see (what’s happenin at an atomic level). Now there is easy access to animations and simulations online that show them what’s actually happening in incredible detail. It really helps them make that connection.

The second major element of the 2007 Digital Education Revolution election commitment was to provide Australian schools with FTTP (fibre to the Premises) broadband with connections with speeds of up to 100 mbps. This was to be delivered as part of the roll out of the National Broadband Network (NBN). At the time, the NBN was intended to be a fibre-to-the-network-node roll out and dedicated funding of $100 million was provided to connect schools to the NBN nodes. This has been overtaken by the Government’s subsequent decision to build the NBN as a full, national fibre-to-the-premises network.

Dedicated funding is being provided to enable schools to more effectively take advantage of the NBN. On 8 August 2012, the Government announced the National Broadband Network Enabled Education and Skills Services pilot at the Sydney Opera House. Some $27 million was provided to 12 projects under the NBN-Enabled Education and Skills Services Program.

In order to demonstrate the potential of fibre connections to schools, the Minister for School Education, Peter Garrett, announced the successful pilot programs during an interactive, online drama workshop with the Bell Shakespeare Company at the Sydney Opera House and students at Willunga High School in South Australia. He noted that the Opera House’s ‘From Bennelong Point to the Nation’ project already uses the NBN to deliver virtual classes in drama, dance and music to students living in remote and regional areas across Australia.

One of the successful projects was the Australian Youth Orchestra’s $1.5 million Digital Connection Trial. The Trial is intended to demonstrate how the NBN can support video communications between city, regional and remote areas for interviews, live auditions and master classes for students –from their homes, classrooms, rehearsal spaces and concert halls.

So, what about the future? Computers and information technology, generally, have a rapid obsolescence cycle. Has this been factored into the Digital Education Revolution policy?

The short answer to these questions is, yes. The original policy commitment envisaged that schools would be able to reapply for capital grants every three years to update and upgrade their technology. Following consultation with stakeholders, the refresh timing was changed to four years. Funding is provided in the current Commonwealth Budget to implement this agreement.

The reality is that we are already into this phase of the program. Schools and school systems are replacing equipment purchased in the early years of the roll out right now. To again take NSW Government schools as an example, current Year 12 students will take their netbooks with them at the end of the school year. The NSW Government is undoubtedly well advanced in purchasing the tens of thousands of new netbooks that will be needed to provide computers to the 2013 crop of Year 9 students.

But what of the longer term future? Will the current arrangements continue forever? Very few Government programs do remain unchanged over the years, and nor should they. The more important question to be asked is, what kind of program arrangements will best deliver the underlying policy objective?

The Digital Education Revolution was always about how to use information and communications technology to improve the quality of education in our schools. The current shape of the program, with its focus on direct Commonwealth funding for the purchase of computer equipment, was determined by a stark reality. You cannot use information and communications technology to improve education if the necessary computing hardware is just not there.

The Digital Education Revolution has delivered a real transformation. Australian schools now enjoy comprehensive access to high-quality equipment and support services. But many educationists believe that the real benefits of information and communications technologies in schools will not be realised as long as the provision of ICT is seen as a supplementary activity, and not a core element of school operation.

The Government is currently examining all elements of its funding for schools as part as what has come to be known as the Gonski review. One of the many issues it will need to consider is how to find the best way of not just maintaining the benefits of the current Digital Education Revolution program, but how to extend and build on those achievements.

Evan Arthur

Latest posts by Evan Arthur (see all)

- Digital Education Revolution – Did It Work? - May 27, 2013

There are 4 comments

Add yoursPost a new comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] Arthur, E. (2013, March 23). Digital education revolution-Did it work [web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.educationtechnologysolutions.com.au/2013/05/digital-education-revolution-did-it-work/ […]

[…] Arthur, E (2013). Digital Education Revolution – Did it work?. Education Technology Solutions. Retrieved from https://www.educationtechnologysolutions.com.au/2013/05/digital-education-revolution-did-it-work/ […]

[…] the Australian government, under the stewardship of the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, started a big push towards making computers available to every upper secondary school student. The program ‘has delivered a real transformation. […]

[…] With technology developing at a break neck speed we need to develop with it this is the case with education. As we make technological leaps and bounds we are seeing the introduction of new pieces of hardware introduced into classrooms. Over the years we have seen this happen with examples such as the Digital Education Revolution put in place in 2007. […]